Secretum Mundi is not so much a publishing company as it is a movement.

As an author of more than sixty books that span many genres – from travel to fiction, and from fantasy to short stories – I believe that all writers deserve to be in complete control of their work.

Over my thirty-year career, I’ve been published by some of the biggest publishers out there. My books have been released in many hundreds of editions, in more than forty countries. Using cutting-edge technology, writers like you and I can blaze a trail to a Brave New World in publishing…

A world in which you can conceive and plan the books you want to write, in the formats you want them to appear, without marketing teams cajoling you to create what they believe will sell, sell, sell.

Five years ago, I created Secretum Mundi as a blueprint as much as it is a publisher. The plan has always been for it to publish one author, and one author alone: ME. As I release my work directly through Secretum Mundi, I want to show you how it’s done.

I’m not here to try and make money from fellow authors. Rather, I want Secretum Mundi to be a space within which writers who have seen the future can share ideas, get contacts, and move briskly beyond the

next horizon.

Tahir Shah

Secretum Mundi is not so much a publishing company as it is a movement.

As an author of more than sixty books that span many genres – from travel to fiction, and from fantasy to short stories – I believe that all writers deserve to be in complete control of their work.

Over my thirty-year career, I’ve been published by some of the biggest publishers out there. My books have been released in many hundreds of editions, in more than forty countries. Using cutting-edge technology, writers like you and I can blaze a trail to a Brave New World in publishing…

A world in which you can conceive and plan the books you want to write, in the formats you want them to appear, without marketing teams cajoling you to create what they believe will sell, sell, sell.

Five years ago, I created Secretum Mundi as a blueprint as much as it is a publisher. The plan has always been for it to publish one author, and one author alone: ME. As I release my work directly through Secretum Mundi, I want to show you how it’s done.

I’m not here to try and make money from fellow authors. Rather, I want Secretum Mundi to be a space within which writers who have seen the future can share ideas, get contacts, and move briskly beyond the

next horizon.

Tahir Shah

Steps To Direct Publishing

Step 1

Manuscript

Write, write, write! Read through your manuscript at every stage and self-edit as much as you can. Remember that direct publishing is about writing the book that YOU want to write.

Step 2

Editing

Your finished manuscript should be read by an editor who will review the structure and form of your book. Additionally, a copyeditor may suggest tweaks relating to language, grammar, and syntax. Factor in time for revisions!

Step 3

Proofreading

Once the content of your book is final, have your manuscript proofread by as many trusted people as possible, including professionals if you can afford it. The principle is that you can never proofread too much – ask friends, family, anyone you can think of to look out for errors or inconsistencies. Keep in mind that the quality of your work must be as good as (or better than) conventionally published books.

Step 4

Format

Choose whether you want your book published in hardback, paperback, or eBook format (or all three!). This will affect book production and upload costs, and ultimately the sales price of your book.

Step 5

Typesetting

Select the design for the interior of your book, working with a typesetter to achieve the right style whilst adhering to technical specifications. Consider the look of any additional pages such as contents, index, appendices, and dedications.

Step 6

Final Proof

It’s best if you can have your final typeset file proofread by at least two proofreaders. Again, the more people you can find to proofread, the better. At this point, you should only need to correct typos and layout errors for the typesetter to rectify.

Step 7

ISBN

Your book will require a unique ISBN for each format published. ISBNs can be purchased individually or in batches from Nielsen in the UK, or Bowker in the US. The ISBN must be featured on the barcode of your cover.

Step 8

Cover

Once you have an idea of the general look and feel for your cover, you can design artwork yourself or purchase a stock image. Write – and proofread! – the back cover blurb text, and commission a designer to create print-ready files (including a barcode). Once the print cover and interior files are ready, you can move ahead with converting them for an ebook edition.

Step 9

Platform

Select which printing and distribution platform/s you wish to use. Each platform will have a different cost and royalty structure (which differs again for ebooks), so compare options. For printed books, consider whether you want to invest in a small print run or stick to a print-on-demand model.

Step 10

Upload Files

Create your accounts on your chosen platforms. This will require personal financial and tax information in order to receive payments for book sales. Simply enter the metadata for your book and upload the final files – your chosen platform will calculate costs and royalties to help you set the sales price.

Step 11

Printed Proof

Order a printed copy of the book and check the cover and interior thoroughly. Check converted ebook files in different reader formats, paying particular attention to any illustrations, graphics, lists and links. It’s very simple to upload revised files should you wish to make changes.

Step 12

Legal Deposit

It’s a legal requirement to send copies of your book to the British Library and/or the US Electronic Copyright Office.

The Writer’s Craft

A selection of helpful extracts on writing and direct publishing as featured in my book,

The Reason to Write.

Container vs Content

My father once gave a lecture at an Ivy League university in New England.

Listening to a recording of it, I can picture the scene perfectly. When he’d been introduced, he informed the students he was going to talk for an hour, just as he’d been asked to do. Then, smiling wryly, he said:

‘But first I am going to let you into a little secret. I’m probably not supposed to tell you this, but I will anyway, because it’s an example of the way I regard the world and everything in it.’

The students glanced up in genuine interest.

‘Now that I have your attention,’ my father went on, ‘I’ll tell you the secret… Although I’m scheduled to talk to you for an hour, I could do the talk in three and a half minutes. I could even do it in two minutes, if you listened hard. But I’m not going to – even though I’d probably be the most popular visiting professor ever to lecture here. The reason is because the Occidental society in which we live confuses container with content. If I were to say everything I had to deliver in three and a half minutes, the faculty which is covering my fee would regard me as a fraudster.’

As promised, my father went on to deliver the entire lecture, and was applauded long and hard at the end. The central theme – of ‘Container and Content’ – shaped the university lectures he delivered all over the world, as well as many of his books, most notably The Book of the Book.

‘Container and Content’ is an idea on which I myself was weaned.

Olden Times

There are all kinds of writers out there, writing all kinds of work.

My key point centres around the way things are, and the way things ought to be.

They’re quite different – like two paths that once ran as one, before forking sharply away in different directions. My mission is to get the paths back to how they were supposed to be – running together like a lovely towpath following the twists and turns of a river… a towpath that did service to the writers first, and to everyone else second.

To understand what I’m saying, I must to take you back to how the great scheme of things were shaped before they went off-kilter. So please bear with me and allow me a little poetic licence.

In ‘the olden times’ (as my kids used to call anything that happened a long time ago), there weren’t many publishers as we know them today. Most of the time an author would write a book, then give it to a printer who would typeset it by hand, print it, and knock it back to the writer, who would go out and sell it to his chums.

Little by little the system took off.

The authors realized they could write a lot more if they didn’t have to spend so much time selling their work. So they gave it to guys hanging around on street corners to sell on their behalf.

Time passed, and the street hawkers made money from peddling the writers’ fresh work. They got themselves kiosks, and eventually fully fledged bookshops. Even though back then books weren’t books as we know them. You see, until the 1830s a book was sold in its raw state – without covers as we have them today. The posh people (who were buying most of the books) didn’t want covers anyway. They would send anything they bought to their binder to have it bound in the uniform livery of their private library.

Years dragged on.

The writers wrote, the booksellers sold, and all was generally good. By now some booksellers were doing so well that they branched out. Instead of just selling printed work given to them by writers, they started representing them, too. Note: it was the booksellers who did the branching out and not the printers – which surely would have made more sense.

A little further along, the bookseller-publishers were doing so well from the arrangement, they started to look for gaps in the market so they could clean up all the more. They grabbed hold of writers whose work was well received, and offered them cold hard cash in return for being locked into publishing contracts.

If I could go back to any time in history, it would be that moment.

The moment the first greedy, self-important publisher got an ingenuous author to sign away his or her rights and – more importantly – to sign away their control.

As you can imagine from my tone, my wish to time-travel was so I could break up the meeting, rip the contract into confetti, and hightail it out of there with the writer.

But I can’t travel back in time, so we’re stuck with a reality path that became a normality path – the path in which writers are told what to write by publishers, or at least how to write it. I know there are exceptions, and not all publishers are ghouls, but the vast majority of them are and always have been.

Of course they are.

Why?

Because the existing model of publishing is like the standard red-light districts I’ve seen throughout my travels. A sordid underworld of brothels, hustlers, and pimps. I’ve seen pimps wearing some very flash outfits and sporting plenty of gold, but they’re still pimps, just as the brothels are always brothels, despite what the sign says.

In the same way, I’ve known publishers who have crème de la crème offices, and who lay on lavish lunches with foie gras and champagne, but that doesn’t make them any less pimpy than they are.

The bad news: Things are back-to-front, because they got flipped way back when.

The good news: Everything’s going to be just fine.

‘Really?’ I hear you asking.

YES! YES! YES!

I can see you hovering over the page, eager to know how I can be so sure. The answer is a single word:

TECHNOLOGY

In the same way technology got authors into a bind in the first place, it’s going to free them from the shackles of bondage.

The Way of Things to Come

Having finished Casablanca Blues, I was an instant novelist.

A novelist who’d made a vow to himself not to allow his work to be hacked around by money-mad publishers ever again.

The only question now was how to release the book. In my enthusiasm to write the novel, I hadn’t given any thought at all to how to publish it.

Shuffling through to the kitchen, I asked Rachana what she thought.

‘Release it yourself,’ she said.

‘How would I ever do that?’

‘You always say publishers are numbskulls, so surely it can’t be as hard as you think.’

‘But who’ll typeset it?’

‘I will,’ Rachana said.

I got a flash of my father pointing to the newspaper article a few days before he died – the one with a photo of an elaborate machine, and the title: ‘The Way of Things to Come’.

There must have been progress on the technology front in the intervening years. Hurrying to the Internet, I googled ‘self-publishing’, and was greeted with a list of firms offering the service. Most of them supplied Amazon, and the other online stores, direct.

Among the sites Google had trawled up was the ‘Espresso Printing Machine’. Rather like an upgraded photocopier, it could print and bind entire books right there and then. I learnt how the machines were being wheeled out in public libraries across the United States.

What was clear was that the technology had moved on in leaps and bounds. The Brave New World was hanging over the conventional publishing model like a death cloud – the same one which had so recently decimated the music business.

Under the new model, an author is asked to choose the format, type of binding, and paper, before being given a unit price. You simply upload a typeset file and cover artwork, and then the platform kicks in.

When a copy of the book is ordered – on Amazon or wherever it is – the order gets forwarded straight to the platform.

Within minutes a single copy of the book is printed, bound, packaged up, and mailed out to the customer. There’s no need for printing thousands of copies, or to schlep them to a warehouse – where they depreciate from the moment they arrive.

That’s only part of the fabulousness of it all.

In the print-on-demand system you can tweak the layouts whenever you like, and simply upload the revised design files at the drop of a hat. That means any annoying typos can be corrected with ease.

Best of all is the cost – or rather the lack of it.

You get your work out there without having to spend much at all.

At the time I first started investigating print-on-demand, I was still very much in touch with the publishers who handled my work around the world.

Messaging each one, I asked for their thoughts on authors who release books direct to the public.

I expected them to meet my enquiries with good-humoured banter.

What came back amazed me.

Every single publisher and agent responded with the most excoriating attack on ‘self-publishing’ – something they regarded as tantamount to treason. They spat the term over and over as though it represented the most wretched concept imaginable.

A seasoned editor at one of my publishers wrote:

‘Any author sufficiently misguided to go down the path of self-publishing will find himself banished and untouchable. For all intents and purposes he’ll be regarded as a leper. The self-published are tainted beyond reproach, and they’ll never be permitted back into the realm of respectable authorship.’

So by going it alone I’d be a literary leper?

Wow, I thought, let’s bring it on!

My plan was to release my first novel Casablanca Blues through one of the print-on-demand platforms that were springing up all over the place. Just to make sure it wasn’t some suicidal route destined for death and destruction, I resolved to start with a trial run.

For someone propelled through life in the slipstream of spontaneous decision, it was distinctly out of character.

But I’m glad it was the route I chose to take.

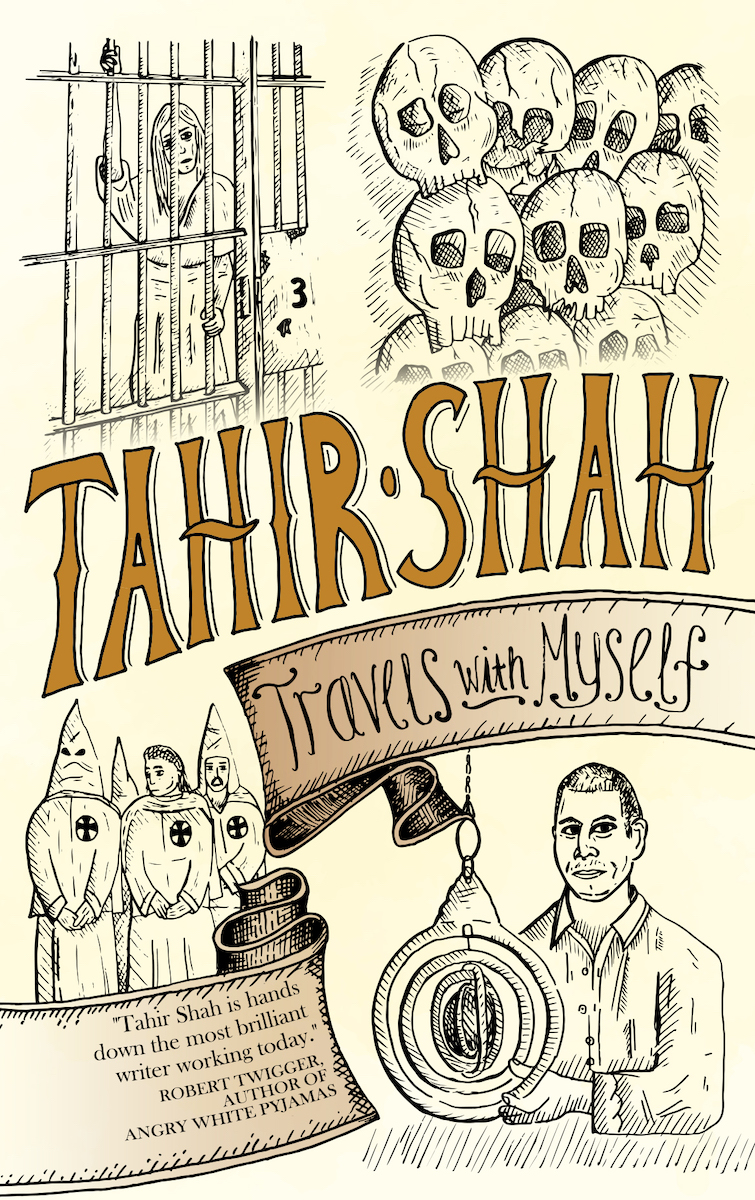

I’d been beavering away for a few weeks at creating a book called Travels With Myself, from my collected journalism and miscellaneous writings. Having compiled it solely for myself, I’d done so without any hope of commercial success.

Being so low key it was a perfect test of the print-on-demand system.

Rachana typeset the book, which turned out to be a respectable four-hundred-page tome. After quite a bit of tweaking, and wondering whether we were doing anything wrong, I clicked the ‘SEND’ button.

The book was accepted by the system, and we were green-lit to route it through to Amazon.

As I was in London giving a lecture, I ordered a copy to be sent to where I was staying.

Next day, a brown cardboard packet arrived.

I opened it up, amazed that it’d arrived so fast.

A moment later I was holding the one and only copy in existence of Travels With Myself.

Survival

While I was a university student living in Kenya, I went on a safari to Maasai Mara – a vast tribal land on the sublime plateau lost on the floor of the Rift Valley.

Late one afternoon we went to a vantage point over a watering hole, and waited as the animals came forward to drink.

A family of warthogs scurried forward from the bush, tails upright, thirst very great indeed.

As we watched them drinking, the other creatures around them doing the same, one of the hyenas raised its head subversively from the surface of the water, and froze.

‘He’s heard something,’ Anthony, my guide, whispered.

‘Heard what?’

‘Wait and see.’

One at a time, the other animals picked up the sense of threat, paused, panicked, and fled.

The only creatures which didn’t react were the little family of warthogs.

As they slaked their thirst, no doubt delighting in having the waterhole all to themselves, a lioness charged out of the tinder-dry undergrowth and pounced.

In the ensuing scuffle, a male warthog was gored. Even though he’d been terribly wounded, he flipped over and managed to attack the lioness with his miniature tusks.

That warthog was outgunned a thousand-to-one.

But still he had a frenzied, frantic go at winning, rather than yielding to the inevitable. After a short tussle, the lioness slunk back into the savannah, dragging the prey as she went.

I commented on the warthog’s bravery – how he’d dared to make a stand against such a formidable foe.

‘When an animal is faced with death,’ Anthony responded, ‘he becomes the bravest, meanest son-of-a-bitch you’ve ever seen. He can’t help it. It’s instinct.’

The publishers were just like that warthog at Maasai Mara.

With their backs up against the wall, they were preparing themselves to fight for their very survival.

From then on, I threw myself into understanding the ins and outs of the new world order, and how it would ultimately be arranged.

If I was going to be the author I longed to be, the one who wrote for himself, I’d have to release my own work directly to my readers.

That was the only way of ensuring total control, and to make certain the volume and range of writing I had in mind would get released as I needed it to be.

Fortunately, I was married to a graphic designer who’d designed some of the most beautiful commercially produced art books around.

Design was one thing, but direct-publishing platforms were another.

Eight years or so ago, when I first dipped my toe in the waters of this enchanted pool, the technology was much more rudimentary than it is now. Every month new formats and bindings came on stream, along with new avenues of distribution.

I like to think that one day someone will pick up this book and gasp at the undeveloped nature of what I’m describing as the potential way of things to come. What’s certain is that the emerging model will continue, and will develop month on month, year on year.

There’s no reason for it not to.

What Do Publishers Do?

I have described how the publishing model we’ve always known emerged from the street-hawkers touting unbound folios two centuries ago. It was a system that came about as a consequence of necessity – one which worked quite well.

The chief defect is of course that the publishers got their hands on the overwhelming control, and made most of the money, rather than the writers.

You may be scratching your head, wondering aloud if you’ve heard any of this before.

Yes, you have.

It happened in the music business a few years ago, when companies started streaming songs for next to nothing. There are plenty of parallels between books and music, and plenty of differences, too.

The point which amazes me is that, with their swollen sense of self-worth, publishers didn’t realize the climate was changing.

Nor, apparently, did mammoths.

At the core of publishing’s existential crisis is a central question:

WHAT DO PUBLISHERS ACTUALLY DO?

Here’s an honest, if unwelcome, assessment:

- Do publishers pre-select the work?

- Rarely. Agents do that.

- Do publishers edit the manuscript?

- Rarely. It’s outsourced to freelance editors.

- Do publishers typeset the manuscript?

- Rarely. It’s outsourced to freelance typesetters.

- Do publishers proofread the typeset book?

- Rarely. It’s outsourced to freelance proofreaders.

- Do publishers print the book?

- Never. It’s printed by a printer.

- Do publishers store the books they’ve printed?

- Never. That’s done by a warehousing firm.

- Do publishers distribute the book to booksellers?

- Rarely. Distribution companies do that.

So, if publishers don’t do any of the stuff above, what do they do?

Here’s the answer to that question:

- Publishers lock authors into brutal contracts.

- Publishers block writers from producing anything except material they think will make the firm a fortune.

- Publishers stifle real creativity and suck up most of the profit when profits are made.

- Publishers seize control and never let go.

- Publishers assert they’re needed in a central and irreplaceable way.

It’s that last point which both amuses and disturbs me the most.

From time to time I stick my head above the parapet and discuss with publishers what on earth they do. These days the debates are never very affable, especially when I give voice to my point that all I ever see publishers actually doing is trying to impress everyone else with self-importance.

Each time the subject is publicly aired, mainstream publishers seem more ferocious and enraged. All I can think is that, like the poor, brave warthog on the savannah in Maasai Mara, they’re fighting for their lives.

I’ve noticed that politicians who are about to be slaughtered in the polls tend to cling to a single catchphrase or policy. Publishers do the same thing.

Over and over they repeat how they’re needed to filter all the rotten writing out there, and select the cream of the crop.

Publishers see themselves as the ‘Men from Del Monte’.

Think about it.

They’re telling us that we need them to make the choice, because without them we wouldn’t have any way of telling what was good and what was bad.

When I bite into a piece of fruit – chosen by the Man from Del Monte or anyone else – I know instinctively if it’s good or bad.

And, if I don’t know, I work it out through my own sense of judgement.

When I hear a song on the radio, I know whether I love it or hate it. I don’t need a producer at a swish record label to tell me whether it’s great or not.

The same goes for writing:

When I read a book that has no identifiable publisher’s name, I decide for myself – just like I do with the fruit, the music, or with anything else.

In a last desperate fight for their own existence, publishers bang on about how they’re providing a quality standard, like a well-loved brand of soup. They claim that by publishing certain authors, they’re giving them the stamp of kudos – the ‘Man from Del Monte’ saying YES!

Three Questions

Three questions spring to mind:

- When was the last time anyone chose a book by the publisher rather than by the author?

- Why do we need publishers to filter, when we have Goodreads and other book community sites?

- Why would a writer who believes in their work need a publisher to extend the comforting arm of kudos – the kind which reminds me yet again of the Emperor’s New Clothes?

Belief

Non-writers like nothing more than whooping and hollering about what they think, doing their best to shunt one’s creative process from the tracks. I’ve never understood it, but I’ve watched it for decades now. Just because someone isn’t creative, they rant on and on about how a writer, an artist, a musician, or whatever, has lost the plot.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The point is that as a creative (as my friends in the advertising business call us), you can only do right. Yes, some things will flop, but you’ll learn from them, and so in many ways they’re likely to be more useful in the long run than the dead certs.

Again, I beseech you:

BELIEVE IN YOURSELF!

The fact you’re reading this book tells me you’re a real writer through and through. As such, you have to be comfortable with experimentation – in the same way I experimented with a series of small test novels like Paris Syndrome and Eye Spy.

Writing is creation.

Just as it’s not about pleasing anyone but yourself, it’s about exploring what works for you. If you need reinforcement on how amazing you are, don’t write books – get a dog instead. But if you’re ready to embark on the greatest journey of self-discovery imaginable, tread the path…

…but do it in the knowledge you’re walking it for yourself.

Editing 1

As with proofreading, it’s essential to get your work edited if you’re releasing it yourself. Most professional writers agree that in recent years publishers have shirked on having editorial work done. As with everything else, it’s chalked down to cost-cutting. This means books with terrible plot holes get launched, like ships with great gashes down the side. The best-case scenario is to find an editor who you like, and to work with them book by book. They will get to know how you write, and what your strengths and failings are. Most importantly, they’ll know to be sensitive with their criticisms, and to polish your work rather than reshaping it.

Correcting

This is important:

If you follow my example and publish work yourself, you MUST be certain there are no typos or obvious mistakes. I can’t stress this strongly enough. Typos and errors of any kind will leave you open to attack – whether you care about condemnations or not. So, it’s critically important to have work proofed numerous times.

I tend to get a manuscript proofed by four different people before typesetting, and then again by another four afterwards. Even then, a typeset book should be read by as many friends, fans, and family as you can muster. You have to explain to them though what they are being asked to proof for. Even though I try to brief friends what I want and don’t want, one or two always give lists of punctuation they regard as inappropriate.

Another key point is that everyone picks up different stuff. There’s a professional proofreader I tend to use who is completely challenged at the job. He misses almost everything – even the most glaring errors staring him in the face. But every time I give him a manuscript, he’ll find two or three mistakes everyone else has missed.

For that reason, his work is worth its weight in gold.

Literary Identity

With the conventional publishing model – the one I’ve railed against throughout this book – there’s almost no way an author can ever reach Doris Lessing’s ‘higher ground’. Unless you’re a fantasy novelist churning out blockbusters hand over fist, publishers will want a book only every year or two. It’s the publishers who created the myth that writers can’t produce more than they do. In a way, the myth reminds me of the great misguided belief in sport – how running a four-minute mile was impossible… before it was run by Roger Bannister.

There’s no question most writers are capable of writing a lot more. The problem is that the publishing houses are incapable of selling more. And, as I’ve said over and over, all they care about is making cold hard cash, so they’ll never release a book that’s not expected to sell in droves.

A great many of my friends are authors. As you’d imagine we are supportive of each other’s work, having watched our various careers and projects trundling along.

Until the new model of direct publishing came along, the only way around the clampdown was to create more than one literary identity, whether the publishers realized it or not. My grandfather, who was running like a finely tuned engine throughout the ’twenties and ’thirties, knocked out up to half a dozen books a year. It was the only way he could survive from his pen.

Raising a small family, and living on his written work, he had no choice but to write under an ever-increasing stable of pseudonyms. His pen names included: John Grant, Richard Drobutt, Raoul Simac, Rustam Khan-Urf, Syed Iqbal, Sheikh Ahmed Abdullah, Bahloal Dana, Ibn Amjed, and even ‘Afghan’.

Experimenting

Writing is about being creative and experimenting, and is not about laying golden eggs all the time. The problem is that the established publishing model is fixated on making money through selling as many books as possible.

As a result, editors and marketing teams will never green-light anything that’s unlikely to pay their salaries.

The one thing publishers detest more than anything else is risk.

As far as they’re concerned experimenting is RISK – in bold capital letters, underlined. They want travel writers to be writing travel, novelists to be writing novels, and everyone else to be working away in their groove. A publisher’s best-case scenario is for their stable of enslaved authors to be writing the same book over and over, so as to extract every ounce of gold from the mother-lode.

Loving Writing

This may sound crazy, but there’s only one reason to write:

BECAUSE YOU LOVE IT

If you don’t love it – and I mean REALLY love it – then there’s no reason to do it. Agreed, a lot of the time an author’s lot is a rough one, fraught with uncertainty and doubt. But it’s one of the most extraordinarily creative mediums humanity has yet devised.

In the years I’ve been writing I have at times found myself forced to do work which bores me senseless. This has included many hundreds of magazine pieces, and a guidebook that reduced me to a whimpering lump of despair.

Even though I was kicking and screaming at the time, each challenge taught me something of great value – forcing me to think in new ways. The more material I’ve written and published, the more I’ve found myself on a wide sprawling plateau…

The Plateau Sublime of Fulfilment.

Standing in the middle of it I feel happy in a deep-down way, as if writing is a best friend, one who’s always with me. Get to that point, think of writing as a saviour rather than a demon to be tamed, and your work changes in a profound and inexplicable way.

Reviews

There was a time when book reviews were everything, and book reviewers were treated like royalty.

In the old days a book would get a tiny window of attention – in which it had to be hyped, reviewed, and piled high in shops.

As with so much, Amazon rewrote the rule book.

There’s no longer the manic need to get media attention for a newly launched book in a single week as there used to be. Reviews are still important for writers (especially if they’re favourable), but not necessarily newspaper reviews.

More important these days are websites like Goodreads, and others where real readers congregate and share their thinking on new and existing work.

The only reason to want reviews in leading media sources is to extract choice publicity quotes to put on the back of a new edition.

As already noted, print-on-demand platforms make it very easy to update book covers at the drop of the hat with a splash of good publicity.

A last point worth making concerns book reviews themselves.

Although I personally steer clear of reading reviews – whether they’re good or bad – even unfavourable reviews sell books.

Agents

In the days of sky-high book advances literary agents had a key role to play, and they played it well.

As much showmen as they were anything else, they could conjure the smell of the bacon… or, rather, the scent of a bestseller-to-be.

A handful of years ago publishing had reached a point at which publishers were getting so many submissions that most insisted that authors go through an agent. That was the moment at which agents became gatekeepers, their self-importance mushrooming overnight.

The key point about agents is that they are working for you.

As such, you mustn’t be frightened to hire and fire – even though they act as though they’re doing you a favour… which they’re not.

Unless you’ve just written the biggest blockbuster fantasy novel in history, an agent will never go into battle for you against a publisher. This is because, while they’re trying to sell your masterwork to the editorial and marketing teams, they’re also trying to offload dozens of other authors on their books.

The only certainty regarding agents is that in publishing’s Brave New World there’ll be no place for them at all.

Blithering Idiots

Commissioning editors are supposed to edit.

That may sound pretty obvious, but it’s not.

Although editors did tend to edit until a few years ago, and were often mini potentates in their own right, they’re largely sidelined now from their original role. These days most editors do very little hands-on editing – which is more often than not farmed out to freelancers. The result is that, physically speaking, books have turned from being content-based, to container-based. Shaped by marketing teams, they’ve become blaring bling-bling objects that scream out at you like packets of breakfast cereal, rather than works of literary merit.

Now, in its last days, the marketing departments hold the real power in the existing model. They have the final word on whether to buy a manuscript, the author’s advance, how and when the book will be launched, priced, and what it’ll look like.

What I’m about to say next isn’t going to win me any friends in the publishing world, but I’ve long since passed the point at which I cared.

So here it is, loud and clear:

For decades mainstream publishing has given jobs to people my father used to call ‘blithering idiots’. Tens of thousands of them over numerous generations. Nice people, but blithering and idiotic all the same – just like those who were once dispatched to the furthest corners of the empire because they were so incapable.

The existing model – the one that’s creaking, straining, and collapsing – sees publishers release tens of thousands of books a year. Almost everything published is destined to fail, with millions of tonnes of newly printed books pulped every year. There’s no other line of business I can think of with such a poor return on products.

Publishers may rant that only they have the track record to select books which will be winners. Absolute nonsense of course. In their desperation to make mountains of cash they commission work which is as wretched to read as it is badly printed.

In the Brave New World where self-released books are the norm, readers will find themselves feasting on the most extraordinary stories available – stories that don’t tick any of the boxes existing publishers hold dear…

Stories which are fresh, original, and unlike anything anyone has read before.

Promised Land

Although I’ve left this section until now, in some ways it ought perhaps to have come first.

That’s because we’re living at a time when publishing is changing, and it’s changing FAST. If you’ve read through the rest of this book you’ll have a pretty good idea of my strong opinions on publishers and the writing craft.

You will know that – as I see it – writing got shunted off the rails it was happily coasting along, and that it’s morphed into the most monstrous machine… a machine which works against real writers like you and me, and promotes containers rather than contents.

This morning, while going against all the advice I’ve meted out to others, I found myself slaloming through Wikipedia on the trail of a fact that needed checking. Next thing I knew, I was reading a piece on the history of electric cars.

With great interest, I learned how the very first commercial car with an electric motor was produced in Des Moines back in 1891.

I can imagine you’re scratching your head, wondering what I’m going on about.

It’s this…

In the same way we are only now getting back to electric car technology, after the internal combustion engine has destroyed half the known world, the standard publishing model is set for the same full-circle change.

What I care about is that the original books are written, rather than more and more third-rate clones of what’s sold before. Beyond that, I care about all the real writers who have been locked out of the system until now.

The original model of book writing – in which authors created work and released it directly to the public – is back. And it’s back in a way our author foremothers and forefathers could have only ever dreamt of experiencing.

Even as I write this, new technologies are conspiring to make it easier for creative people to release work in incredible new ways. An overwhelming disdain for publishers appears to have put me at the forefront of the new model.

The model which, as I say, is an old one rather than something new. The technology of the first electric cars is surely almost unrecognizable to modern engineers, but I bet the concept is the same.

In the same way, the new revolution in writing for oneself and releasing work directly runs along age-old lines – but the technologies that bring the model to life are new.

Through coming months and years the spell will be broken, and the monolithic publishers of old will disintegrate as the real writers look on, and reclaim control.

Over the last handful of years, I’ve worked to champion the new model – one which will serve me as a writer, and others like me.

Please understand: I am totally uninterested in setting myself up as a publisher. Doing so would go against everything I stand for. After all, my message is all about freeing writers from the bondage of slavery, so that they can have faith in themselves.

The plan is to offer authors a blueprint which will enable them to conceive, write, and then release work on publishing platforms using new technology. I’ll do my best to explain what I have in mind and map out how I think it will work.

Plenty of my author friends are published by mainstream publishers, and many of these friends are thrilled to bits with the attention they receive from the literary world. Despite this, I have no intention of going back to the broken old model. The only reason I’d do so is if I were written a cheque with so many zeros I’d have to count them twice. I’m not trying to lure anyone to the Promised Land with me, preferring both new and established writers to make the decision for themselves.

As I have said, I’m interested in the Salinger Brigade – writers who write because they can’t not write. In the same way, my interest is first and foremost in writing to satisfy myself rather than merely to attract the attention of others.

The business of empowering authors is not so much about giving them strength, but rather about taking the strength from those who have held the reins of the creative process until now. Like all imaginative people, authors are frequently tortured by self-doubt. Far more damaging than self-doubt is the way the conventional publishing system has conspired to keep all but a handful of writers down, rather than striving to build all worthy writers up.

The lifeblood of real writers are letters, words, and paragraphs.

As such, they must be in the creation zone, the realm in which every author worth their salt ought to reside. Once there, you must stay there. Flounder, and you’ll end up in the long grass. Ask yourself repeatedly if you’re still in the slipstream, and whether there’s anything you can do to be more streamlined.

And, never, ever take for granted that you’re in the writing zone.

Forget about how many copies of your new book you’re likely to sell, or what to put on the cover. Forget, too, what the readers are going to think about it when it’s released.

For now the process is centred around you, the real writer, doing what you love.

The New Model

Seven years ago, I set up the publishing arm of the Idries Shah Foundation, the charity established in my father’s name.

In that time our team published more than four hundred editions from my father’s corpus – including hardback and paperback volumes, eBooks, audio books, as well as limited and even hand-printed editions, too. I have used the same model to release my own work – both my backlist and a flood of new projects.

The model we have come up with has served our purposes, but may not serve yours. The beauty of the Brave New World is that it allows a fully bespoke service. You’ll be able to keep total control over your work, use the format which best suits you, and release it as and where you like. At the same time, you won’t have anyone telling you how or what to write. Everything you do will link to everything you’ve done and all you have planned for the future. As a consequence, you’ll be able to conceive a great series of books if it’s what you have in mind, without the spectre of it being canned by men in suits or the marketing team.

First Draft

As I’ve already written plenty about what’s worked for me, I’ll keep this section pared down as much as possible.

I’d like to reiterate that following the new model means you can experiment as much as you like. Even when your books has one on sale, you will be able to re-edit it, and release different versions. My suggestion is to sit down at the start and jot down what you want to achieve, and the story you want to tell. Get that rooted firmly in your mind. Write it on a sticky note and position it on the edge of your screen. Look at it all the time during the writing process and ask yourself if you’re on course.

Plan the book even if you’ve written others before. As I’ve said, I always do a plan if only so I can go off-piste. Plans don’t have to be detailed or particularly long, but rather provide a structure. In the same way a portrait painter will sketch the outline and features of a face before picking up a brush, the plan allows you to maintain consistency. I try to make my plans as orderly as I can, with headings, subheadings and so on. During the writing process I add to them by hand, listing anecdotes, information, and details.

I used to make a wordage list, too, and would tape it to the corner of my desk. At the end of each writing day I’d fill in the daily number and tally up the total. Looking back at these tallies, something strikes me… All is well as long as I write every single day. But the moment I take a break, or don’t keep to the daily wordage, I lose precious ground. For this reason I like to rope off three weeks or a month to write a large-sized novel, so there won’t be any chance to get sidetracked.

Again, there is no right and wrong when it comes to a daily wordage. And, unlike me, a great many successful writers can knock out a book in fits and starts. When I embark on the journey I have to know where the end point lies – the distant horizon. Or, rather, the not-so-distant horizon. Like a mountaineer standing on a summit, I like to get a fleeting glimpse of where I am going, even if it’s blurred. My method is to slog like a maniac to get to it, even if it means I’m crushed by the journey.

Once or twice I’ve written the last page or so early on and worked my way towards it. At least then you know where you’re heading. It worked well and provided me with a fixed end point so that I could stop worrying about it.

With the new models in publishing no one is going to be telling you how many pages to write. As with everything else, you’ll have freedom to decide for yourself. If you haven’t written books before, my advice is to talk it through with a writer friend. Or, even better, to find a book you know and like, which resembles what you have in mind, and to use it as a blueprint – like one of those paper patterns people used to buy to make their own clothes.

A tip which has worked well for me is to keep writing when I’m on a roll, and to later divide the book into several parts. It’s much easier to do that than to write the first part, then cool down and start on the next instalment. As you’ll see, the new system is set up for you to try out formats, layouts, and writing styles that suit your work – rather than having them foisted upon you by an editor.

Cleaning

Once you have the first draft done, it’s time to go through and clean it up. Rather like cleaning up an apartment which has had wild, rampaging students trash it, you need to get a grip on exactly what you’re going to do. So, just as you might sweep all the mess onto the floor, straighten the cushions, and then vacuum up, I’d do something like this:

- Read through once and make sure the spellings and basic grammar are right.

- Correct glaring errors and holes in the storyline or plot.

- Check the character descriptions, and tidy up clunky passages.

- Go through the manuscript again, balancing every single sentence. If you are unsure what to do, read it out loud line by line. Or, as I’ve described, use the speech function so the computer reads highlighted text.

When editing your own work it’s easy to get hunkered down when you should be moving briskly ahead, or depressed by passages you think are second rate. If this is the case, set yourself specific goals – like an hour to correct a certain wordage. While it’s true you can hide dull passages in a book, it’s best not to. In truth, every sentence should earn its right to its spot on the page. If it doesn’t add to the story or the overall atmosphere, you should think about deleting it. That may be too hardcore for many writers, but most great writers nail it down.

New writers are impatient. They want their work to see the light of day immediately, and get it into their heads that anyone preventing this stands against them. In reality, a book takes time, and a book which has been rushed is very likely to have fault lines running through it which will be challenging to correct later on. The way I regard it, time spent cleaning and correcting is profoundly valuable, because it gets your work up to the next level. But it’s not only about polishing the text, so much as it is mastering the craft.

Writing is as much an expertise as cabinet-making or karate. It’s something that is learned through application and diligence, perfected through hands-on experience. You can only ever get good at it by doing it, and definitely NOT by talking about it. Yes, there are certain propensities which will make the journey easier, or will make you more of a ‘natural’, but most of it is hard grind. Along with the grind, a second sense slowly emerges through which you develop an appreciation of what works and what does not.

One of the things I have learnt is to give a work in progress the right gestation period. Not all projects are the same. A novella may only require a couple of days of consideration, while a long series of books could well take years of thought. The point I am trying to make is that books take time. Of course you can rush them, but they’ll suffer as a result. Don’t get me wrong – I am all for writing fast. It keeps up momentum. But I fully recognize the value of planning and editing as well.

Although I have sometimes been impatient to get a new book out there, I’ve come to learn the huge value of holding back, waiting, and reworking text after a gap of months, or even years.

In writing this I’m reminded of an elderly Czech violin-maker called Fredic I got to know while down and out in my early twenties. I’d go and sit in his workshop at the ‘bad’ end of London’s Portobello Road. I’d watch him, and would listen to him. But most of all, I’d gaze at all the half-finished instruments hanging on the walls.

One afternoon I asked Fredic why he never seemed to start on an instrument and finish it in one go. Peering over at me, the craftsman seemed to smile through the corner of his mouth, as though he’d waited years for the question.

‘Everything I’m doing in here is thought out,’ he told me. ‘It may seem like chaos to you, but it’s all planned. All these instruments are on an adventure. They know it, and I know it. But neither they nor I quite know where the journey will lead, and that’s where the magic lies. The only way to make certain they complete the journey is to be sure they’re perfectly prepared. To do that, I give them time, and myself time.’

I asked Fredic what he meant.

Brushing his tabby cat off his armchair, he slumped down onto it.

‘Every day I come in here, open the shutters and make some tea,’ he said. ‘If someone was watching me from out there they might think it was the same day lived over and over. But they’d be wrong. Every day is completely different. That’s because I’m different, the weather is different, and the date and time are different. All that means I see and experience things differently.’

For years I turned Fredic’s words around in my mind, half-wondering whether I understood them at all. But gradually, over time, I did – and they made perfect sense.

Look at a painting, a page of text, or even a half-finished violin a thousand times. To the untrained eye they may appear pretty much the same. But to the questioning mind, the mind which created them, subtleties will be apparent. The ability to pick up on the subtleties allows you as the creator to shape them from the inside out.

Just as Fredic would hang a work in progress on the wall until he was ready to continue with it, I have learned to do the same with my writing. At any one time I have at least five works in progress sitting on the mantelpiece.

Eventually, I get to a point at which I am ready to pass the manuscript on for a first read. It’s not a moment I particularly savour, and giving it to the right person is important.

Editing 2

I tend to pass all new work on to my close Argentine friend, Agustin.

There are many qualities I admire about him – among them his kindness, his patience, and his ability to see detail with one eye and the big picture with the other. But, most of all, I value the fact he doesn’t judge. Like everyone else I’m sensitive about unveiling new work, and don’t like having to do it at all. I’ve sometimes considered following the lead of J D Salinger, who left a storeroom filled with completed novels. But then again, he had written Catcher in the Rye.

So, I send the manuscript over to Agustin and forget about it.

Actually that’s a lie – I don’t.

I pace up and down, checking the time incessantly, wondering what’s keeping him from getting back to me. It’s not that he’s slow in reading but rather I’m skittish with nerves. I realize this doesn’t tally with my need to write for myself, but I’ve sworn an oath of honesty.

Agustin usually comes through with two lists of comments. The first are general and relate to structure, and the second are specific points relating to detail, or prose that could be cleaned up. An important point to stress is that I give Agustin my work for two reasons – the first is that I regard his suggestions highly. The second, more important, is that he knows my work and he knows me. He’s read all the books I’ve written and has a clear understanding of how I think.

I usually dread receiving Agustin’s notes, because I’m fearful he’ll think the book is a waste of space. Thankfully, he’s always exceptionally accommodating. If he says a passage could be improved he’ll usually make suggestions how it could be done.

That’s a big point…

An editor is there to help you tweak your work and hone it. I know next to nothing about bonsai trees, but I like to think of an editor as one of those doting bonsai guys – like Mr Miyagi in The Karate Kid. They’ll observe the tree intently for what seems like hours and only then will they make a few careful snips – so the bonsai’s inner beauty is brought out.

My advice to any writer is to get an editor who will follow them from one book to the next. The key thing is that they get to know you and your work, and that first and foremost they enable it to shine in a way you’ve wanted.

In the days when I was published by the big-name publishers on either side of the Atlantic, I had a string of editors assigned to me. They were all forgettable, except for one – Caroline Oakley at Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Her extraordinary skill at honing text equalled Mr Miyagi’s expertise with the scissors. Rather than chopping and changing everything (as a great many of them wanted to do) she would make changes at a micro level and somehow achieve the desired result.

I should say that writers are not usually editors. I for one am hopeless at going through text and offering sensible advice, and I dislike being asked by people to evaluate their work. Prodigious readers aren’t necessarily good editors either. They tend to get sucked down so deep into the work that they can’t see the wood for the trees. The best editors I have known tend to have a kind of split personality, enabling them to evaluate in different ways – in the way Agustin does for me.

Once your editor has gone through the manuscript it’s up to you how much to take on board and what changes to make. As I have moved along the arc of the writing process, I’ve tried to get my books in the shape I want them before even showing them to Agustin. I snip away lose ends, plug holes in the plot, and try to reshape anything I know will get Agustin’s attention for the wrong reasons.

At one time I had an overly enthusiastic editor who used to return manuscripts covered in thick red pen. It was like having my homework graded by the teacher from hell, and made me very jumpy indeed. The only way I could make sure anything saw the light of day as I wanted, was to use the ‘Monkey’s Paw’ technique.

For anyone who doesn’t know it, the story goes that an artist was asked to paint the portrait of a particularly fussy member of the aristocracy. Knowing full well she would criticise every last detail of the finished work, he painted her right hand as a monkey’s paw. When the picture was unveiled, the duchess at once seized on the fact that her hand was not a hand at all. Horrified, she went on and on about it. In doing so, she overlooked the other failings of the work.

As a writer who had to jump through hoops laid out by my publishers, the Monkey’s Paw was useful for drawing away the fire. With the new model of direct publishing there’s no need to devise complex ruses to save oneself.

Another thing I should say is that editing is not proofreading. First time authors tend to get mixed up with this. An editor is concerned with the structure and form of the work – questioning whether the characters arc in the right way, and that the themes develop as they should.

The fact most mainstream publishers are cutting costs – replacing editors with marketing teams – means that most books no longer get edited well at all. These days most editing is done by freelancers, who tend to get paid by the hour. As budgets are continually being slashed, they’re permitted to bill less and less – meaning a great many manuscripts don’t get more than the roughest read-through.

Proofreading

Once your manuscript is structurally sound it’s ready to be proofed.

How much work will be involved depends on what kind of a writer you are. I do my best to clean up glaring errors before sending a book to Agustin, but even so there are always plenty of them left.

A key point is that no author writes text devoid of clunking mistakes. The more you write, and read through a text, the more blinkered you become to it.

A good proofreader is worth their weight in gold. In my opinion you’re well advised to pay for at least one professional proofing. As with editors, it’s advisable to try and use the same people if you think their work’s good. I have a team of proofreaders I rely on – a mixture of professionals and friends.

As I noted earlier, different people read in different ways. Some proofreaders are tuned to pick up grammar, while others are especially good at hunting for three different spellings of the same name.

The main proofreaders I use – who will correct this manuscript before it gets to you as the reader – are all excellent at grammar, spelling, and at rooting out all kinds of inconsistencies and errors. What I appreciate about them most is that they all seem to read in a slightly different way. As a result, they each pick up different points for me to note.

Once the book has been proofed by several professionals, I read it through again, twice. The first time slowly, checking the weight and value of the words, and asking myself whether the sentence structure could be improved upon. The second read through is much faster – usually a case of my computer reading aloud to me as I sit in a chair, listening.

Then, when the last corrections have been incorporated, I print out a final version and put it with the other manuscripts to be bound. It’s a silly tradition of mine, and one that seems to be dying out.

When I moved to Morocco a decade and a half ago, I found a business card in my grandfather’s papers – the business card of a bookbinder in Rabat. Having published seventy-four books during his lifetime, my grandfather would have his manuscripts bound in red morocco, a tradition that my father continued, and that I myself have acquired. For the last decade and a half I’ve used the same atelier as my grandfather, the son of the son binding batches of my manuscripts each spring.

Typesetting

With your manuscript ready to be typeset, it’s time to dance a jig around and congratulate yourself. You’ve made it much further than most people, and the pleasure of seeing your work in print is about to begin.

This is the point at which the path of the conventional publishing model and the Brave New World go in opposite directions. So say goodbye to all the writers destined to lose control. You won’t be seeing them again. From now on you’ll be waited on hand and foot in a bespoke tailor shop, with your every wish and whim catered for.

First things first.

You have to get a sense of what you want. The best way to do that is to go to the biggest bookshop you can find, and to browse like you’ve never browsed before. Look at the books in the genre where you would expect to find your book, and then look at a dozen or so other genres as well.

Try to find editions that excite you in terms of their physical look. Check out the covers, and the text on the back of books. Most importantly for now, look at the interior layouts.

There are a few things conventional publishers absolutely loathe.

Now I think of it, there are more than a few – there are masses of things which get on their nerves. I know because I’ve been at the sharp end of their displeasure time and again. Their many pet peeves include when authors want to:

- Use a particular font or design

- Suggest a cover design

- Give ideas on marketing

- Know what the retail price will be etc., etc.

Almost no author I’ve ever encountered has ever got involved in the layout. It may be because they don’t care, but my thinking is that it’s because they’ve never been asked.

I’ve always taken an interest in how books look, what kind of paper they’re printed on, and even (don’t judge me) how they smell. It’s because I love paper books. I appreciate eBooks and think they’re great – because they get people reading – but at heart I’m a paper man.

The thing which gets me excited like nothing else is a well-printed book with off-white paper, wide margins, and ink that doesn’t rub off on your fingers when you read it.

Unless you’re living on a different planet from me, you would have noticed that a great many paperbacks have slid down a steep slope into The Abyss of Low-Grade Rot. More and more publishers are doing something I regard as sneaky – they’re blowing the budget on printing the cover, and wrapping it around a splotchy, fifth-rate mass of paper little better than newsprint.

While browsing you may come across a book you really like and think it might work well as a source of inspiration for physical style. My suggestion would be to buy a copy, or at least take a few photos with your phone. In the feeding frenzy of bookshops – whether they be bricks-and-mortar or online – every title’s trying to grab your attention. As a result, they all seem to cancel one another out. Once in a while you’ll spot something which sucks you in – more often than not through its pristine simplicity.

When you’ve done the research, it’s time to find yourself a typesetter. This is one of the many areas publishers like to pretend is their preserve, and theirs alone. Just as car mechanics don’t like anyone but their own fraternity to have anything to do with engines, publishers disapprove wholeheartedly of writers who want to get involved.

The way I see it, creating a book is about so much more than merely writing the thing. As someone who loves books, and the writing process, I am enthused down to the marrow of my bones by every single detail and stage. For years I was locked out, told it wasn’t my place – that I was meddling in something which didn’t concern me.

How stupid I was, because for years and years I believed them.

Finding a book designer is just about the easiest thing on earth. As with anything, there’s a massive selection of designers – some charging eye-watering amounts for what is (in my opinion anyway) rather basic work.

Most of the book designers I have on my team are based in India. They’re efficient, highly skilled, and they follow the template I have asked for. A top tip that’s worked well for me is to get a book designer to scope out the first twenty or thirty pages in the font I like.

I tend to use Bulmer, the font I used for my limited-edition novel, Timbuctoo. Over the years I have developed a general look which pleases me, involving masses of uncluttered prelim pages and extra space. There are plenty of typesetting details to indulge yourself with should you feel inclined. Just like having made-to-measure clothing, you can for the first time have any cut or finishing you like.

There are plenty of design pet peeves I swear by, which drive everyone else mad. Top of the list is hyphenation. I get the shivers when a word is split needlessly across two lines. Mainstream publishers go for word-splitting because it speeds things up, and typesetters cost money. Another of my bugbears is widows and orphans – stray words on the first or the last line.

You’ll need a checklist of various standard bits and pieces, which include:

- A copyright page – which you can copy from a published book, substituting your own details.

- An ISBN number, which you get online (some POD platforms charge for them, while others provide them for free).

- An optional name of a publisher and a logo.

- A list of social media links to put at the end, along with an invitation to your readers to write reviews.

Typeset Proofing

Once the book is typeset, the designer will email you a PDF file, and you’ll get a first glimpse of your book looking like a book.

It’s an exciting moment, one that never ceases to thrill me. Right away you’re likely to see mistakes, which is quite normal. The magic of typesetting is that it allows you to see, with fresh eyes, work you have read a hundred times.

An important thing to remember is that changing text which has been typeset isn’t like changing words at the manuscript stage. Every change made from now on has a knock-on effect. The best-case scenario is to only make alterations if they’re absolutely necessary.

The priority is for typos, and glaring errors – like incorrect capitalizations and indention, misaligned headings, and so on. If at all possible, try not to rewrite because it’ll drive you – and the typesetter – crazy. Make sure to put in the time before sending the manuscript to be laid out, so that the typesetting stage is a final polish.

But, again, there will be corrections – especially when you get others to proofread the typeset book. My advice is to work with a typesetter who is happy to incorporate revisions made over two or three drafts of the typeset version. Go through the laid-out pages carefully yourself and mark anything which leaps out at you. When you’re done, ask the typesetter to incorporate the changes. Then, at that point, email the pages to friends and family and, if you can afford it, to a professional proofreader again.

Unless you send paper copies of your typeset book out (which most people don’t bother with any longer) it’s worth downloading a good PDF viewer which incorporates editing tools, and checking your proofreaders have the same version, too. That way they can mark corrections and use digital sticky notes. By this stage I usually find it’s fine to send the book out to multiple people at the same time, as they’re hopefully not going to pick up massive mistakes. Make sure to brief family and friends in particular on what you want – otherwise they’ll flag up far too much. It’s essential they understand you’re only looking for typos and other glaring mistakes.

Covers

Most authors who have been producing books for a while have a best and worst cover. My best cover was for my travel book Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and featured an Indian godman. The worst cover (for the same publisher) was for the paperback of my first book, Beyond the Devil’s Teeth. A wretched mishmash of psychedelic confusion, it was so bad I hid under my duvet for three days, moaning like a wounded wildebeest. I would have insisted the publisher change the cover, but I couldn’t. The contract said they had the right to come up with anything they wanted, although they had to show it to me in advance.

By the time I delivered my second book, Sorcerer’s Apprentice, I had written in the right to refusal – a point which made the publisher very jittery indeed. They came up with yet another monstrous cover. Wild with anger, I found the godman image. On the back of it, the book was a success. As with every other detail of the creation process, the Brave New World of direct publishing allows you to make all the decisions, and to have covers you love right from the start. If you’re planning to write a stream of titles, or at least a series, then it makes sense to have continuity in the book covers.

I myself have used various artists over the years, and am currently releasing my new work with a plain white look. The reason is that I don’t give a damn if anyone buys my books at all – I wrote them for myself. And, as every other title being released is vying for your attention, it’s quite pleasing to be the only writer whose cover is understated and low-key.

Print-on-Demand

I’m a HUGE fan of the new print-on-demand (POD) platforms, and have watched them evolve in a handful of years to hold the position they currently do. Things are moving so fast in the print-on-demand industry that I’m not going to try and give a comprehensive breakdown of the entire sector.

What you need to know is that POD platforms take your typeset book and cover files, as well as key bits and pieces of information, put it all together and spew it out as a finished book. There’s a wealth of formats available, and every month more and more choices come on stream. The way POD works is that – as the name suggests – when someone orders a title from Amazon or elsewhere, a copy is printed specifically for them and shipped out. Almost too many to mention, the advantages include the ability to update the files at the drop of a hat, and the fact that the books aren’t rotting in a damp warehouse somewhere. Better still, you can change the covers whenever you like, insert pages of rave reviews at the front, and even print limited editions for a certain period of time.

Pricing

When the Net Book Agreement ruled, the price of new books used to be set in stone. With its abolition, anyone could sell any book at any price. Supermarkets piled chick-lit and fantasy fiction high and sold them cheap. Publishers wheezed and groaned at getting pennies rather than pounds. Then one fine morning they were hit with the single word that changed everything: Amazon. Overnight, the idea of standard prices came to an immediate end. As I understand it (believe me, no one except for Amazon really seems to understand it), the friendly online shop of everything gives different prices according to their algorithms. I have no idea whether this is myth or reality, but what I hear happens is that Amazon will show you a price they believe you’ll be tempted by. And if, for instance, you put a book in your online basket and let it stew there for days or even weeks, they’ll suddenly drop the price. After all, they’d rather you buy from them at a low cost price than go to anyone else. The blessing of the POD system though is that you get to set the profit margin you’re comfortable with.

Someone told me there was a book for sale online entitled How to Make a Million By Selling a Single Book, and that it was priced at a million bucks.

Alas, I can’t find it.

Perhaps it sold!

Bound Proofs

In the old days of publishing, there were fixed (if unwritten) rules. These included the principle that reviewers wouldn’t go anywhere near a paperback, but rather expected hardbacks. The reason for this – as everyone in the business knows – was that book reviewers are paid next to nothing. I should know – I’ve done it. They’re expected to supplement their derisory earnings by selling the boxes of brand-new books which turn up on their doorsteps day and night.

These days publishers often go straight to a paperback edition, bypassing the hardback incarnation altogether. It’s confirmation of how things are changing, and changing fast. Until a few years ago most publishers didn’t dare send out finished paperbacks to reviewers – for fear of being laughed out of town. Instead, they’d bind up a quantity of proof copies – a special soft-covered early version… an uncorrected proof.

I’ve always had a thing about uncorrected proofs. It must be because they’re prepared in very limited numbers – sometimes no more than a dozen or two. If you’re still being represented by a conventional publisher you know your stock value is high if they’ll churn out a good big batch of proofs.

The point I want to make is that with the POD platform you can upload your own proofs, order as many copies as you need, hand them out privately to family, friends, reviewers, bloggers, inspirers, or anyone you like. Then you simply update the files (removing the words ‘Uncorrected Proof’) and load them onto the POD platform you’ve decided to use.

You can also print a few copies with an additional page inserted into the prelims. The page can announce something like, ‘For Private Circulation Only. Limited to 50 copies.’ By numbering and signing the books you’ve created an instant special edition.

Crowdfunding

The one point on which crowdfunders all agree is that there’s no such thing as free cash.

As one seasoned crowdfunder told me:

‘Crowdfunding can be a useful tool, and even a thing of wonder, but it’s damned hard work.’

Below are a variety of pointers accumulated from a number of authors who have used crowdfunding successfully:

- The first thing to remember is your campaign will only be as good as your social media network. Developing a database of family, friends, and others, is a MUST. Crowdfunding is about engaging them, making them feel a part of what you’re setting out to achieve, and taking them along for the ride.

- The second thing to get your head around is what your project is all about. There’s no point in launching a half-baked idea – crowdfunding is founded on clear goals, and there’s no goal so important as the project description itself. Work hard at it. Study the market, checking what similar books there are in the genre, and how yours will stand apart. Hone your project brief over time, rounding off the corners, and don’t be afraid to return to the drawing board if it simply doesn’t pass muster.

- ‘Innovation’ is a key buzzword in the crowdfunding world. Be innovative in coming up with ways your followers will want to get involved. This includes thinking of lots of rewards they’ll fall over each other to lap up.

- Rewards come in all shapes and sizes. A campaign could feature, for example a schedule such as this:

- Signed copy of the book £15

- Signed copy with donor’s name printed in the back £20

- Signed, numbered limited edition with illustrations £40

- Limited edition with folio of artwork £60

- Limited edition with invitation to private launch £75

- Dinner with the author £150

- Hand-corrected proof of the original manuscript £1000

- Another thing to get right is the amount of funding you need. A lot of campaigns flounder because they’re asking for too much. However hard they try they never quite manage to break across the halfway mark. It’s sometimes advisable to lower the bar so progress appears all the more impressive. The advantage of this is that would-be funders are likely to be wowed by a campaign which is well subscribed.

- Most crowdfunding campaigns have at their heart a video of the author lifting the veil on the project. In some cases, these films are sleek marketing tools worthy of a high-end advertising firm. Most of the time, however, they’re passionate, honest explanations of what you are trying to achieve and why.

- Bear in mind you have to factor in the cost of packaging your book up and shipping it out. If it’s a big, weighty tome then the mailing costs will eat into the funds raised. Always add a margin to take into account higher costs than expected.

- Every step of the way you must take your supporters with you. This includes posting updates on as many social media platforms as you can stand, championing your progress and, more importantly, giving thanks for all the support.

- Involve funders by asking them which design they think works best, and even which ending they prefer. A rapport with supporters is worth its weight in gold, and will form the foundation of the next campaign.

- Although most authors who resort to crowdfunding do it because they need the cash, some don’t. Instead, they mount campaigns because they’re such a sure-fire way of guaranteeing sales once their book is released.

- The final point to make is crowdfunding only hits the high-water mark when the author has put everything they can into the campaign and pulled out all the stops.

Procrastination

Procrastination is part of the creative process.

However terrible it may seem, it’s critically useful – because it’s the dream zone proving that we need inspiration in order to create. There’s a danger in trying to eliminate procrastination, one that may well lead to far less original and inspired work. My advice is to allow oneself regular structured procrastination breaks. Safe zones, they’re when you can turn your phone on, guzzle espresso, stare out the window, and allow your mind to slip away into a faraway realm.

The way I perceive it, daydreaming and procrastination are the waking forms of nocturnal dreaming. As such, they are the place at which the blurred mind creates wonder by zoning out of focus.

I’ve written about Wikipedia elsewhere, and will touch on it again here. As I usually research information as I move ahead, I generally resort to checking material online, or in reference books kept to hand. What works for me is to write on a scrap of paper exactly what I need to know before embarking on the online search. Diving aimlessly into the enchanted Wikipedia pool is accompanied by the danger of never emerging intact.

Giving in to procrastination, I give myself a challenge. Setting a timer and an alarm, I try and dredge up ten choice nuggets of information online within fifteen minutes.

Questioning

If there’s one golden rule of book writing to nail up above your desk, it is:

NEVER QUESTION YOUR ABILITY!

They say if you want to dance like a pro you should practise as though no one is watching. The same is true for writing. If you want to take the craft to a whole new level, write as though no one will judge you. And, remember to write for yourself.

Every time you question your ability, you smother the flame of creativity a little more. Remind yourself over and over you’re amazing. If you ever doubt it, read a random page grabbed from your Shelf of Wretched Reads.

Remember this: the more you write, and the more differing projects you work on, the stronger your literary muscles and the greater your skill will be.

Writing is a journey which promises no clear destination.

Rather, it provides a route to beyond the far horizon that will be as magical as it is unexpected.

Thinking Big

Something rooted deep inside me has always urged me to think big, or rather bigger than big.

I just can’t help myself.

It would be so much easier for me to drift through life beavering away at small projects, but the universe has conspired for me to reach far and high. As a result of this delusional calibration, I have dozens of books in the pipeline at any one time.

It’s worth remembering here that I am writing for myself. And, although it will always be published, I have no intention to please readers or publishers – only myself.

The great thing about releasing work directly as I do is that you can design projects from the ground up and grow them in entirety, exactly as you want. In the same way that Andy Warhol had ‘The Factory’, the writer who releases work directly can experiment on any scale they like, trying their hand at any genre or technique.